The Royal Monastery of San Lorenzo de El Escorial is a complex that includes a royal palace, a basilica, a pantheon, a library, a college, and a monastery. It is located in the town of San Lorenzo de El Escorial, in the Community of Madrid, and was built between 1563 and 1584.

The palace was the residence of the Spanish royal family, the basilica is the burial place of the kings of Spain, and the monastery founded by monks of the Order of Saint Jerome. It covers an area of 33,327m² on the southern slope of Mount Abantos. It was conceived by King Philip II and his architect Juan Bautista de Toledo, as a multifunctional complex, both monastic and palatial. A colossal work of great monumentality, El Escorial is the crystallisation of the ideas and will of its driving force, Philip II, a Renaissance prince.

East Side – going towards the window

E1

The background is ribbons above and scrolls below.

E2

The background is ribbons above and scrolls below.

E3

E4

E5

E6

E7

E8

The background to this portrait is ribbons

E9

E10

E11

E12

E13

E14

E15

This image is framed in scrolls

E16

E17

The background is ribbons above and scrolls lower down.

E18

E19

E20

The background is scrolls. The woodwork has suffered damage to the subject’s nose.

E21

E22

The background is scrolls. The woodwork has suffered damage to the subject’s nose.

E23

E24

Very little background, perhaps a couple of scrolls at below the seat.

The woodwork has suffered damage to the subject’s nose.

E25

The background is scrolls.

E26

The carving has suffered damage to the nose.

South end – left to right looking south

S1

S2

The carving’s background is ribbons above and scrolls below.

S3

The background is scrolls.

S4

In an email on 21 January 2026 a member of staff at Escorial advised “Unfortunately, the seating in the Old Church has suffered several vicissitudes since its creation in the second half of the 16th century, and the missing misericord was lost over the centuries and is not preserved in any other part of the monastery.”

S5

S6

S7

The carving has suffered damage to the nose.

West side – from the window

W26

W25

The background is ribbons above and scrolls lower down.

W24

W23

The background is a mixture of ribbons and scrolls.

W22

W21

W20

W19

W18

W17

W16

A background of scrolls above and ribbons elsewhere.

W15

The woodwork has suffered damage to the subject’s nose.

W14

The woodwork has suffered damage to the subject’s nose.

W13

W12

W11

W10

W9

The woodwork has suffered damage to the subject’s nose.

W8

The woodwork has suffered damage to the subject’s nose.

W7

W6

W5

W4

W3

W2

W1

The Old or Provisional Church was the most important area of the building during the initial stage of the construction of the Monastery. It was used provisionally as a church from its completion in 1571 until the Basilica was ready in 1586. The first burial chamber of the Spanish Habsburg family was also located beneath its chancel. Philip II’s first quarters were located at the back end and above them was a small upper choir with simple stalls crafted by the French carver Rafael de León, where the friars prayed for the deceased. From 1591 onwards the church was used as a chapel where burial services were held for members of the religious community. For this purpose, its structure was converted into the open space visible today, with jasper steps and rails and the current stalls, which were adapted from the former upper choir stalls by the carpenter Martín de Gamboa between 1591 and 1592.

Gamboa was highly regarded by the congregation and specialised primarily in furniture making. His most notable work was the carving of half the seats in the main library in 1589. He also created a catafalque (a raised bier, box, or similar platform, often movable, that is used to support the casket, coffin, or body of a dead person during a Christian funeral or memorial service) for the funeral rites of the kings and the altarpiece for the church of San Bernabé.

In the last two decades of the 16th century, Gamboa’s work in service to the crown in the Monastery was particularly noteworthy. He is listed as the successor to José Flecha, with an annual salary until his death. Flecha, an Italian sculptor and woodcarver, was one of the most prolific and important artists to have worked at the Royal Escorial Factory. On 9 February 1600 Gamboa requested permission to retire to his home in Vizcaya.

However, Maria Paz Aquilo says Martin de Gamboa only took part in the choir stalls as an appraiser appointed by the King. She says:

In the descriptions of Father Siguienza, Friar Andrés Ximénez, and Friar Francisco de los Santos, the choir stalls are not attributed to their creators. It was Rotondo who, in 1861, based on Father Siguienza’s notes, attributed their design to Juan de Herrera and their construction to José Flecha, with a team comprised of Gamboa, Aguirre, Quesada, and Serrano. From then on, all descriptions and studies have cited them as the work of these masters.

The Faces

There are 59 stalls and 58 misericords. There are 26 stalls down each side and seven at the window (south) end. Misericord S4 is missing; it is the seat under the elaborate wooden pediment in the centre of the south end clearly intended for the most important person present, either the senior clergyman or the King. This seat shows the construction of the misericords that remain. There may be shadows of two different sizes of misericord carvings.

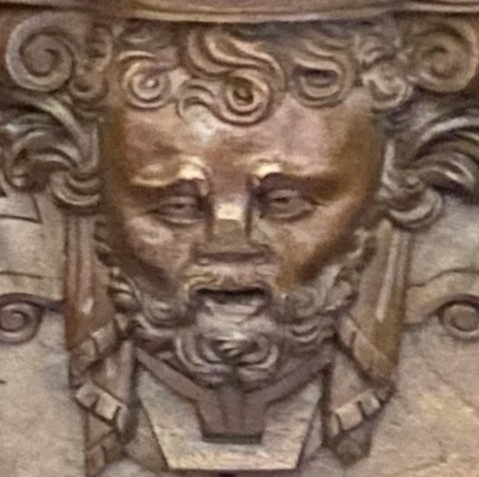

E21 and W21 are non-representational. The remaining 56 images are misericords are of faces without supporters and largely devoid of extraneous elements, a feature that suggests a common origin but may simply indicate a clear brief. While it is clear that the majority of the misericords are of the same hand, a number differ in style depending on your criteria.

Backgrounds of ribbons and scrolls are the norm. Thirteen of the 56 images (E3, E4, E8, E11, E16, E20, E23, S1, W3, W9, W16, W20 and W23) have ears that stick out in a manner that suggests a common authorship – and perhaps an earlier style of work. The number of faces looking out is fairly evenly divided with those looking down.

Caricature E9 has an unusual nose which appears to resemble a cork. W25, which is not a caricature, appears to have the same style of nose. If this feature were present on other examples, it would explain the noticably high number of carvings (thirteen: E2, E3, E4, E6, E7, E11, W3, W5, W6, W8, W9, W14 and W15) that have suffered damage to their noses.

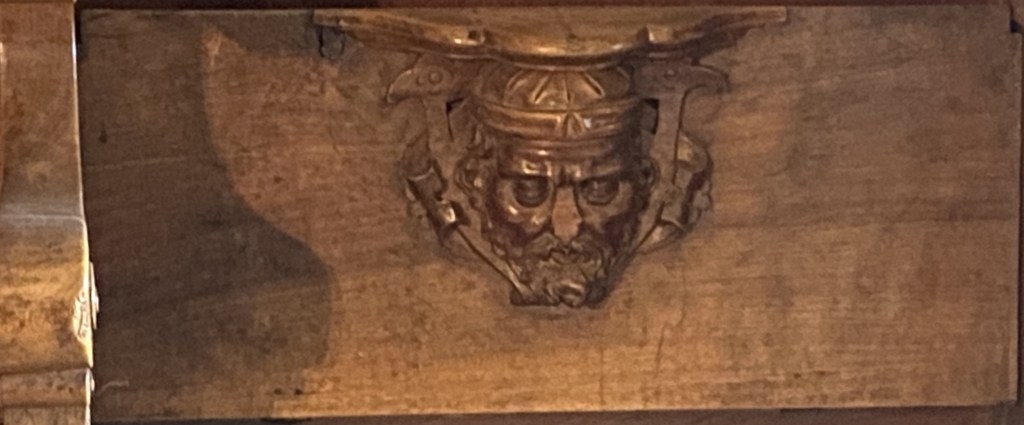

A large variety of headgear is present. Some of it appears to reflect the Moorish presence in Spain. Some of it reflects the fashions of the day; The sixteenth century was one of the most extravagant and splendid periods in all of costume history and one of the first periods in which modern ideas of fashion influenced what people wore. Some of the larger cultural trends of the time included the rise and spread of books, the expansion of trade and exploration, and the increase in power and wealth of national monarchies, or kingdoms, in France, England, and Spain. Each of these trends influenced what people chose to wear and contributed to the frequent changes in style and the emergence of style trendsetters that are characteristic of modern fashion.

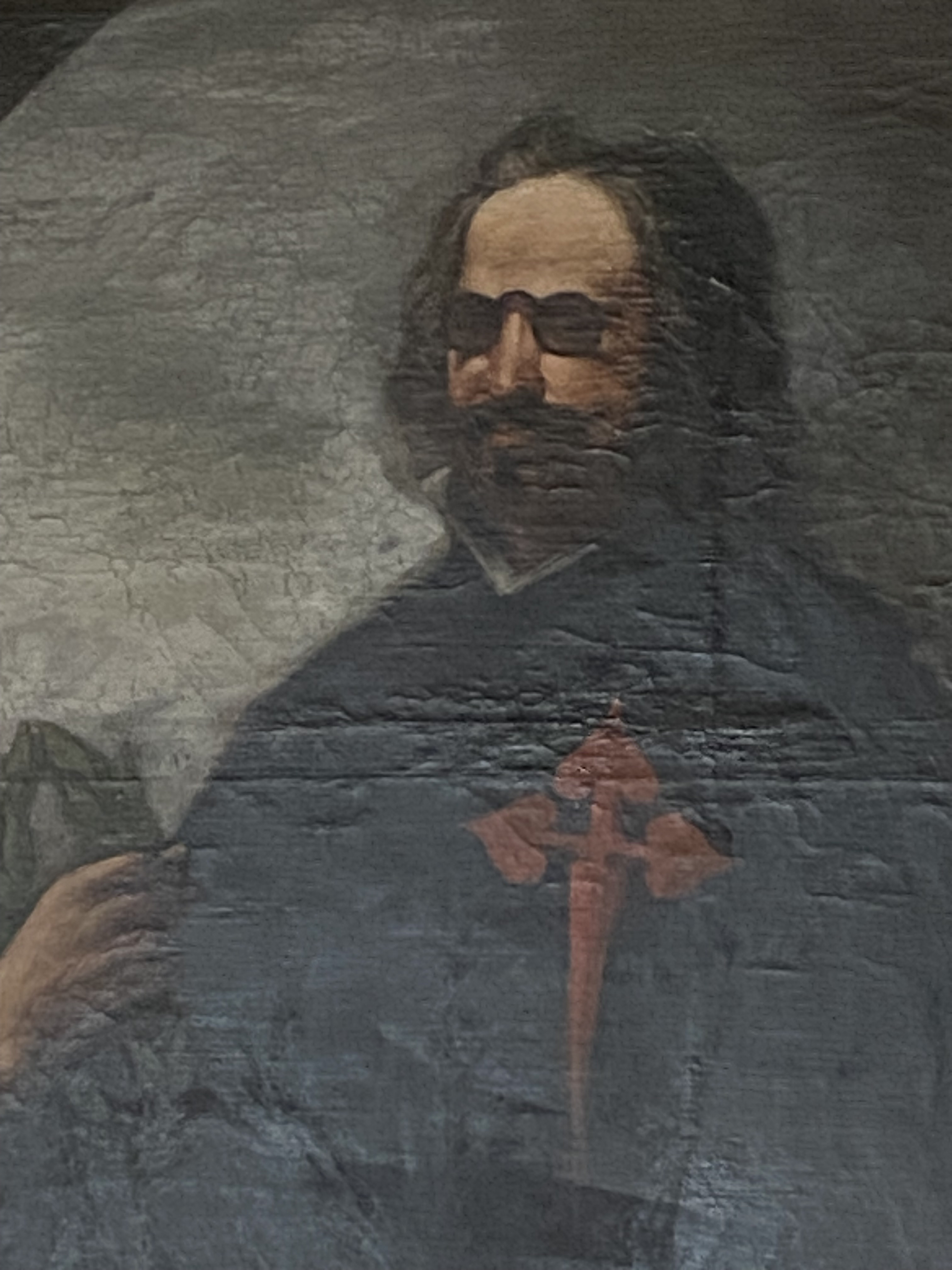

So were these guys? Portraiture rarely exists in a vacuum so one can conjecture that they are people known to the creators of the misericords. Of the 56 faces, half a dozen (E1, E5, E9, E14, W15 and W17) can be described as caricatures or fantastics. But the rest are fairly straight-forward portraits. Combine this with the practice of artists of including themselves when the opportunity arises and one can speculate that it is the woodcarver himself who is shown in image E14 sticking his tongue out at us.

What of the others? S4 is missing which is a pity as it might have given us a clue as to what was appropriate under the seat of a VIP. It might not have been diplomatic to show the King’s face so close to monks’ bottoms but a number (noticeably E15 and E24) have a royal feeling to them. What about the architect Juan Bautista de Toledo? Like the King, contemporary depictions show him with the short beard that is also fashionable today and a common feature of the images.

E10 and S3 look to be women but otherwise the assembly is solidly male.

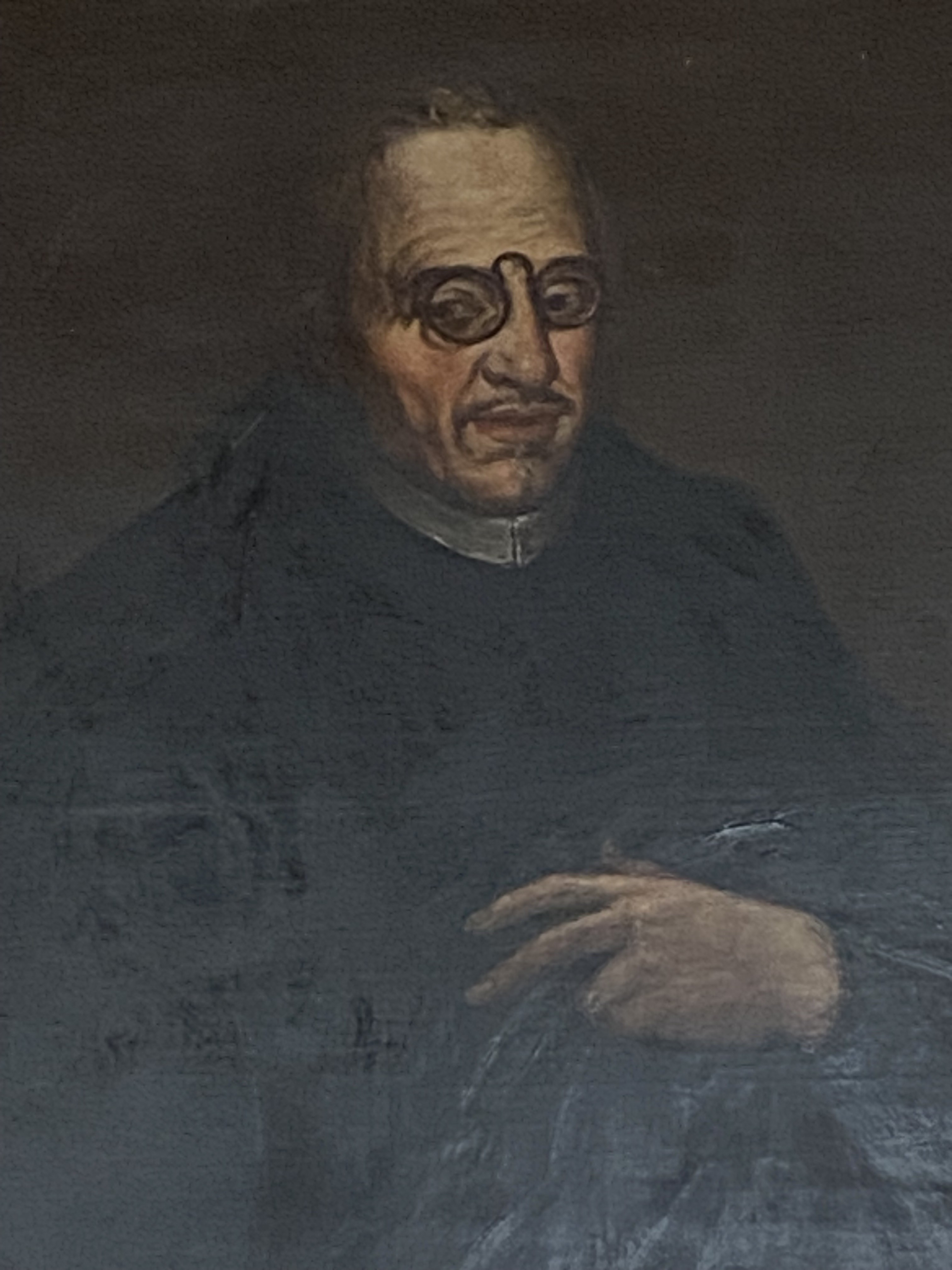

E1 is wearing spectacles but this is not as radical as one might think in 16th century art; by the 15th century, the depiction of spectacles in European art (an invention from the late 13th century) became common, especially with the increased demand for eyeglasses following the invention of the printing press in 1450. A significant number of works feature spectacles in 15th-century Spanish Gothic art, not only in painting and sculpture, but also in miniatures and choir stalls. Spectacles appear associated with two main themes: the image of Saint Jerome, the great scholar who translated the Bible into Latin, and the death of the Virgin Mary surrounded by the apostles, although they also appear adorning the figures of prophets, evangelists, and ecclesiastical figures.

Image E1 is reminiscent of portraits by Antonio Ponz found at El Escorial. Ponz (1725 to 1792) was a key figure in Bourbon cultural policy and worked on the collection of works and relics for the Library of El Escorial, completing its portrait gallery and copying some paintings by Italian masters.

E2 is wearing a steel helmet of a style worn during the 16th century which originated in Spain, known as a cabasset (in Catalan) and capacete (in Spanish). Like the morion helmet, with which it is often compared, it was worn by infantry in the pike and shot formations. It was popular in 16th-century England where it was used during the Civil War. Several of these helmets were taken to the New World by the Pilgrim fathers, and one has been found on Jamestown Island.

Pike and shot was a historical infantry tactical formation that first appeared during the late 15th and early 16th centuries, and was used until the development of the bayonet in the late 17th century. This type of formation combined soldiers armed with pikes and soldiers armed with arquebuses and/or muskets. Other weapons, such as swords, halberds, and crossbows, were also sometimes used. The formation was initially developed by the Holy Roman (Landsknechte) and Spanish (Tercios) infantries, and later by the Dutch and Swedish armies in the 17th century.

Sources:

- Dr Umer Hameed;

- millinerytechniques.com;

- Bexhill Museum;

- Gafas en el arte español del siglo XV (I) (Glasses in XV century Spanish art (I)) JJ Barbon and A. Sampedro, Ophthalmology Department, San Agustín Hospital of Avilés, Asturias, Spain;

- La Silleria del Coro del Monasterio de El Escorial (The Choir Stalls of the Monastery of El Escorial) Maria Paz Aquilo;

- Carpenters and Cabinetmakers of the Monastery of San Lorenzo El Real in El Escorial Manuel José García Sanguino;

- wikipedia Real Monasterio de San Lorenzo de El Escorial; Morion (helmet)

and the visitor information in El Escorial.